Learn Programming: The Philosophy Of Syntax - For Thinkers, Hikers And The Visually Impaired

Wednesday • May 14th 2025 • 6:39:58 pm

Let’s begin with a small, gentle truth.

Programming languages don’t hide their secrets. In fact, they’re shockingly direct.

You don’t need symbols, tags, or strange markup to do math. You simply say:

Two plus two. Just like that. No mystery.

In JavaScript, this is written as:

2 + 2

And it just works. Just like you’d say it out loud.

Try multiplication? Use an asterisk:

2 * 2

Division?

2 / 2

It’s natural. Like talking to the machine, and being understood.

Now here’s where it starts to feel like real power.

You can take the result of that math, and store it. Give it a name. Keep it. Reuse it.

To do that, you need a special word—a keyword. In this case, the word is:

let

We say:

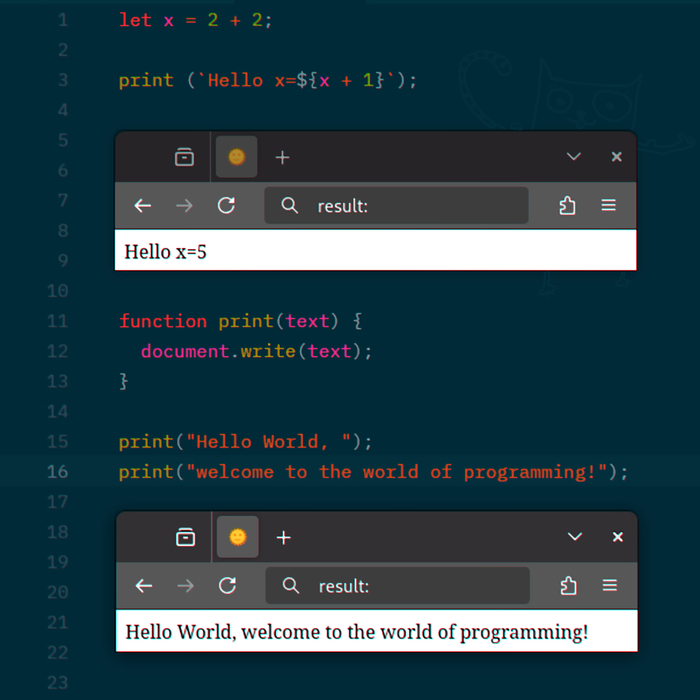

let x = 2 + 2

This says: Let the variable named “x” be equal to two plus two.

Let… x… equal… 4.

Keywords like let are built into the language. They’re part of the language’s soul. They act like traffic signs—clear, simple instructions that help both humans and machines understand what’s happening.

Let’s pause here.

Why do programming languages even need keywords?

Because without them, everything would be chaos. Imagine reading a road map with no signs. Or trying to follow a conversation where every word means ten different things.

Keywords bring clarity. They are fixed, sacred words—memorized, standardized, and honored by the language.

When you use let, you announce: “This is the start of something being stored.”

There are other keywords too, like const, which means “this value should not change,” and var, which is older, and nowadays, rarely used.

But more important than what each keyword does… is the deeper fact that keywords exist. That’s the real lesson here. They are a kind of contract between humans and machines.

Now, what about text? Not numbers, not code—but simple, human words.

In JavaScript, we use quotes to hold text.

Why?

Because if you typed:

Hello world

The computer would panic.

It would think “Hello” was a variable. It would think “world” was another. And it wouldn’t know what to do.

So we wrap text in quotes—a clear signal that says: “Hey! This is not code. This is a string—a sequence of letters.”

You can use:

- Single quotes:

'Hello' - Double quotes:

"Hello" - Or, for something very special: backticks:

`Hello`

Each has a purpose.

Single quotes feel like something private, unchanging. Double quotes are more standard—used for general messages. Backticks, though… they unlock something magical.

Backticks allow you to write multi-line text.

And even more, they let you mix code inside your text.

To do that, you use a symbol that looks like this:

$followed by{}

This says: “Insert some code here.”

For example:

`Hello x=${x + 1}`

This will take your variable x, add one to it, and place it inside your string.

If x was 4, the final message becomes:

Hello x=5

It’s a small miracle.

And it only works because we use clear, simple markers:

Backticks to show we’re writing a string, and ${} to say,

“This part is live. This part is code.”

Now a quick note on punctuation.

At the end of most lines, we write a semicolon: ;

Why?

Because it tells the language:

“This thought is complete. Move on.”

It’s not always required in JavaScript, but it’s a good habit, especially if you ever move to languages like C or C++ where it is required.

Let’s talk about brackets.

Brackets are not decoration. They are structure.

- Round brackets

()are used for parameters—extra info you give a command. - Curly brackets

{}are for bodies of code—chunks of logic that belong together.

Curly brackets are huge. They define where your code begins and ends. They also define what variables are visible and where.

So when we say:

if (x > 4) { }

We’re using:

- The if keyword to introduce a condition.

- The round brackets to say what that condition is:

x > 4 - And the curly brackets to hold the code that runs if that condition is true.

Even if the body is empty right now, this structure is pure philosophy.

It says:

Here is a decision. Here is the logic behind it. Here is what happens next.

Let’s go deeper.

Many programming languages have built-in keywords like let, if, or function.

They are reserved. Sacred.

You can’t use them to name your own variables or functions. That’s part of the contract we mentioned earlier.

It helps both people and machines process your code more easily.

Now here’s where you become a creator.

Let’s talk about defining a function.

A function is a reusable piece of logic. A custom command you invent.

We use the keyword:

function

Then we give it a name—called an identifier.

Let’s say we name it print.

We want it to show a message on the screen.

We say:

function print(text) { document.write(text); }

Here’s what just happened:

- function — our keyword, announcing a reusable block of code.

- print — the name we chose.

- (text) — a parameter. This is like a placeholder. Whatever we pass in will take this name.

- { document.write(text); } — the body. It uses a built-in browser feature to display the message.

Then we call it like this:

print("Hello World");

Or:

print("Welcome to the world of programming");

You’ve just taken your first step into programming. Not just typing code—but understanding the language of logic and clarity.

This is a moment that can change your life. So here’s an important instruction:

**Listen to this chapter again. Maybe thirty times. ** Each time, you will understand a little bit more

Keep a pencil in hand. Jot thoughts. Practice your function keyword and brackets.

And never forget:

You’re not just learning a skill. You’re learning a way to think.

Welcome to the world of programming